I hurried to become an American like it was my destiny.

The first weeks and months in the United States unfolded in surreal fashion. People looked like they’d jumped out of the Sears catalog that once filled my daydreams. They talked too fast, but I noticed they could slow down too, enunciating each syllable like that would help me. I liked car rides—so goddamn fast and smooth. There was a machine that washed your clothes. Shampoo for your hair, plus conditioner! Buttered toast sprinkled with sugar. TV was in color and on all hours of the day. I watched The Price is Right because I understood the numbers, and I pretended to understand Happy Days because I laughed when the live(?) audience laughed. Every house even came with a room just for the cars.

To be more American meant being less Vietnamese—the only way to fill up this cup was to dump out what was already in it.

I formally changed my name to Fawn when I got my citizenship. It never occurred to me or my then-Vietnamese husband to give our three kids Vietnamese names. His real name was changed to John, for God’s sake. His mother enrolled the kids in Sunday school to learn Vietnamese because she knew it’d be the only way they’d pick up the language. I felt bad for them. From personal experience, I knew the meanest teachers on the planet were Vietnamese Catholic nuns. That class lasted maybe three sessions.

I was generally annoyed with all things Vietnamese. Except the food. And except the beauty salons—cheap and they knew how to cut Asian hair. I just had to endure hours of Paris by Night playing on the TV—how could anyone listen to these insufferable singers and watch their gaudy display? Worse was the whiny cải lương, a type of “modern folk opera.”

My mother, apparently, was too old to assimilate. I can’t tell you how many times we told her, Mom, this is not Vietnam. Stop doing that! My sister called once and said, “Guess what your mother did at Costco today? She poked a hole in the salmon package to smell it!” I also couldn’t understand why she squatted in the kitchen when we had perfectly good countertops.

I nearly died at sea to be here, so I couldn’t be bothered with my mother’s failure to get along.

Then it happened. I allowed myself a hint of pride when someone said to me, “You don’t have an accent at all… thought you were born here.” The cup was full—I’d become a full-grown American.

What also happened was that my three Vietnamese children couldn’t talk to my mother or any other Vietnamese person who didn’t speak English. This remains one of the saddest failures on my part. Other Vietnamese parents my age have children who are fluent in both languages and have beautiful Vietnamese names. Outside of a handful of dishes, my kids don’t know much about Vietnamese culture because it had become foreign to me. I’ve tried to explain it away, saying I was only 11 when I immigrated. But that’s not honest. The truth is I actively distanced myself from where I came from. Would this have happened if my parents had come over at the same time? I don’t know. They didn’t get to leave Vietnam until 15 years later, so I basically grew up without them.

Undoubtedly I was stupid and arrogant. Too dumb to realize I could embrace both cultures. Too arrogant (and dumb) to believe that the Sears catalog lifestyle was better. I deprived my own children of their roots, all in one swift generation.

I like listening to Vietnamese music now. My favorite is still Khánh Ly, but I’m finding other wonderful artists too. The folk genre I once dreaded—cải lương—has suddenly become heartbreakingly beautiful because it’s storytelling. Stories about family and love, war and famine, honor and sacrifice. I now call my mother when it’s not even her birthday or Mother’s Day. She laughed when I told her I learned the benefits of squatting from a CrossFit routine.

Sabrina, my youngest, plans to spend a month in Vietnam later this year. I hope she’ll get to learn and celebrate this most beautiful country where her parents were born. We are truly a rich nation when we celebrate and honor all cultures.

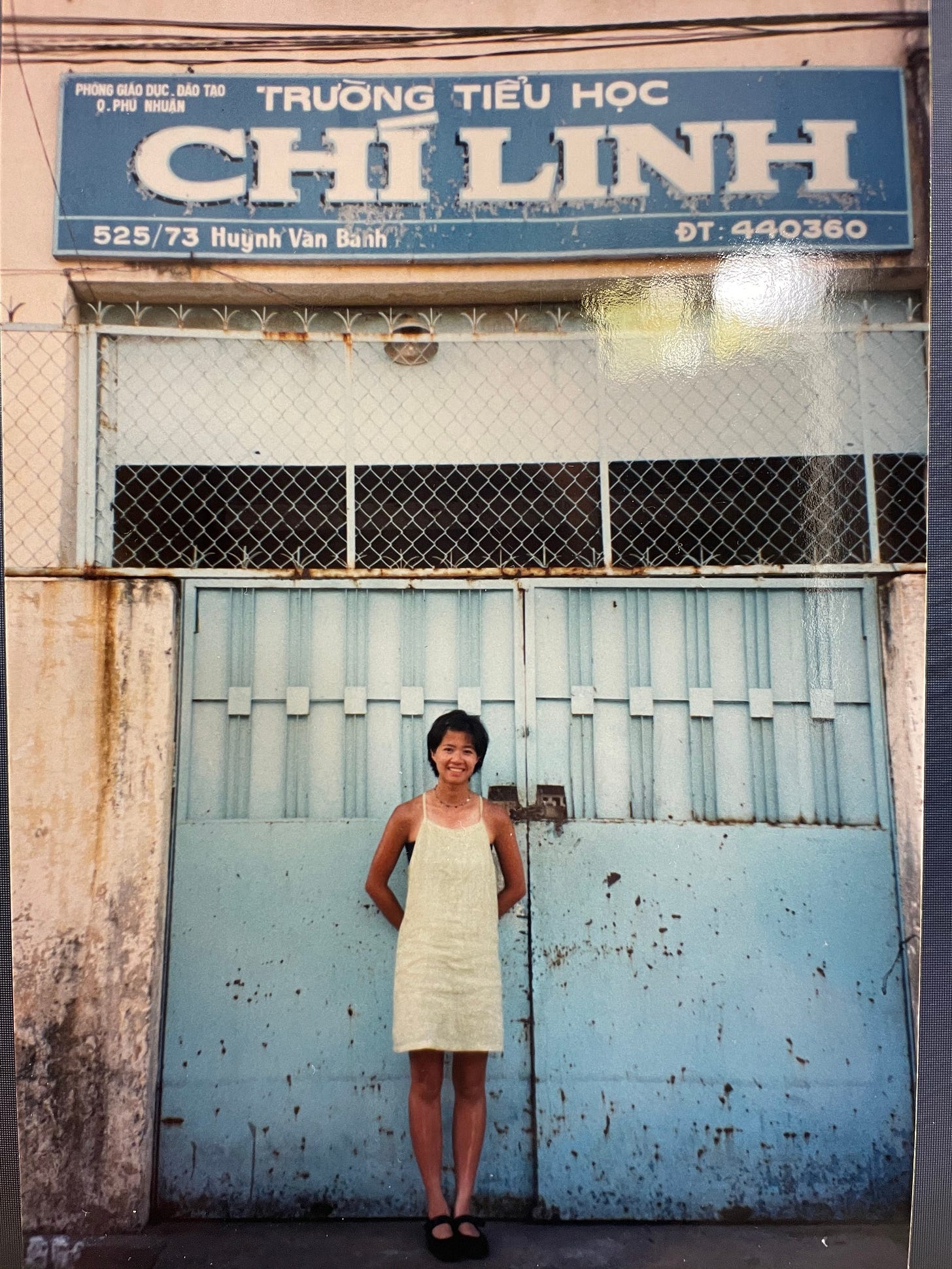

Saigon, 1997

I was 11 when I left in 1976. So I was 32 when I returned and visited my old elementary school. The name had changed, and so had all the street names.